TURN YOUR BACK ON THE SHORE TO UNDERSTAND THE SEA

Simplicity has no baggage.

I’m sitting in a kayak in a hidden cove somewhere in the Andaman Sea’s Mergui Archipelago. This mostly uninhabited string of reefs and islands extend 200 miles along Burma’s coast—an 800-isle Eden the size of Vermont. Since time immemorial, Mergui’s waters have been home to floating nomad families, the Moken, who live most of the year on kabangs, houseboats made from big hollowed-out trees.

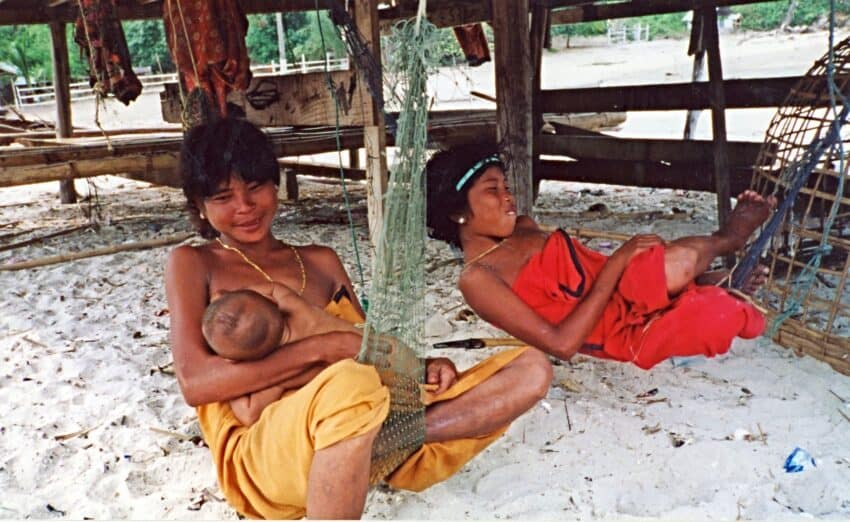

The Moken belong to no country, carry no ID, and speak their own language. The gypsies drift in groups of at least six boats, each vessel housing one family, usually made up of three generations. They wed young, and the community builds couples a boat, wherein the newlyweds can start their own family.

These floating villages migrate between temporary moorings. The Moken use traps, nets, and spears to hunt turtles and collect sand worms, shellfish, and clams. They also swim deep into submerged caves harvesting sea cucumbers for export to China and Japan. Without modern scuba gear, they dive as deep as 80 feet, equipped with only a mask, fins, and a long hosepipe which acts as a snorkel. These houseboaters have no concept of making rent or “meeting you on Wednesday.” They have little reason to make or keep appointments.

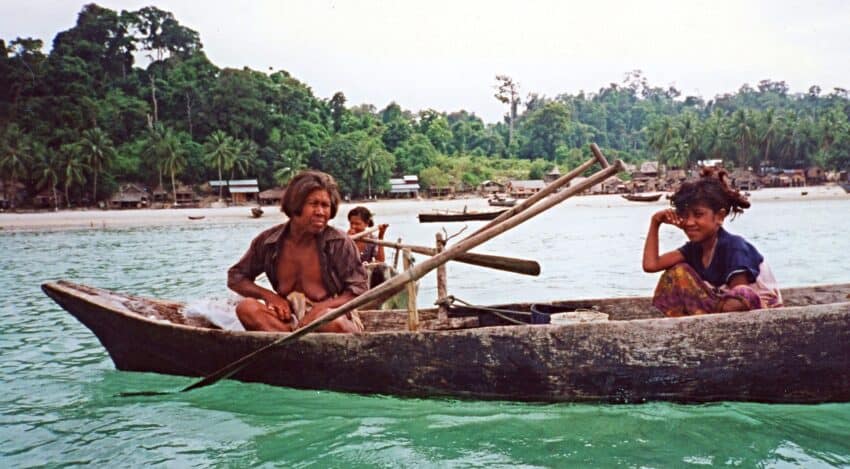

By kayak, I glided through lush mangroves and into two-story-high sea caves looking for the Moken. It took me, my New Jersey friend, and our guide Tham (“Tom”) days to find these elusive people who are born, live, and die at sea. Encountering them on land, we found the invitation to exchange confidences rare, but approaching our first seagoing Moken in a kayak seemed to give us a bit of credibility. I paddled up to a band of very tan families in small dugout canoes. Seated with paddles across their knees, they wait for the tide to go out.

An impossibly beautiful woman with broad cheeks and shiny long black hair sat alone in a tiny canoe. Her smile reveals teeth stained dark red with betel nut. “How’s the fishing?” I ask her. Tham translates my question into Burmese, and a group effort translates it into Moken. “Fish scared away—now over there,” nods the woman.

I turn to my friend to jest about their sea-bound life being one way to avoid paying rent. When Tham mistakenly translates the quip, an elder glances our way, winces with gentle but searching eyes, and speaks. Tham says something lost or found in translation: “Don’t rent space in your head to just anyone.” Rewind a few centuries, or advice ahead of its time?

This universe is a medley of mountainous islands, craggy coastlines, desolate beaches cut into steep-sided limestone pinnacles, and conical upthrusts capped by forest and jagged rocks. We paddle around rock-tower islands, their faces tide-chiseled with gurgling tunnels through which powerful surf ebbs and flows. The roller-coaster tidal action alerts mudskippers and rock crabs to scuttle about the stone facades. Flying fish bounce like skipped stones on the propelled current into dense, partially submerged trees. We follow them.

We time ourselves to ride high tide into mangrove tunnels and then exit on low tide through a vine-encased artery. Massive roots, twisting and intertwined around and above us, form a mangrove church, light twinkling through clusters like rays through stained glass. Not having encountered any more Moken for days, I sit in the sand eating a bowl of rice. The only time I’ve thought about home in a month was having just snorkeled against a fierce tide, colliding with stinging jellyfish traffic.

Back on the move in the kayaks, we approach a kabang, smoke rising from its stove. The boat noses up to my kayak, and a wiry man emerges from beneath the thatched roof wearing a curious glance. He looks at Tham. Tham looks at me but says nothing. The interaction with this seagoer shows there is more binding us than separating us. We are, after all, floating. A gesture is made. Tham decodes it as an invitation to board the kabang. The one-room interior resembles a live-aboard vessel belonging to a boat mechanic—basic but prepared.

Half of all Americans live within 50 miles of their birthplace—the Moken spend their entire lives on it. The kabang is a carved, canoe-like hull supporting a wooden frame secured by bamboo pegs and rattan rope. Thatched palm leaves make the roof and sails. The mini Noah’s Ark is as versatile as a studio apartment, with many items serving double duty, such as tables used as chopping blocks and hammocks becoming fishing nets. I point to various items—stove, bed, fishing spear—and mime their uses. Each guess receives a nod. Open on both ends, there is a sturdy feel to the boat.

These ingenious gypsy rigs, balanced and light for their size, are designed to safely carry a family of up to eight through vicious Indian Ocean storms. Though they look rustic, their naval technology has mystified sea traders, pirates, and anthropologists through the centuries. Mokens focus on pride in the face of scarcity. Kabangs symbolize the ultimate clutter-free existence, a formalized “letting go” that uses identical scroll designs on the bow and stern to illustrate the mouth-to-exit digestive process that holds onto nothing permanently. In another era, this sage design announced to pirates, “We have nothing to steal.” It’s freedom dictated by the whims of the sea.

When the man (who is both a father and a son on this boat) hosting us joins our conversation, he chimes in via Tham, “The sea is the children’s playground and teacher.” Family activities revolve around the boat, just as western families’ revolve around kitchens and TV rooms. Their homes just happen to float. Despite living on the move, they live connected—connected to the water, connected to the stars, connected to the seasons, and connected to each other.

The Moken may be the last link to the indigenous Southeast Asians who survived the Ice Age by taking to boats 10,000 years ago, when the region was submerged in 300 feet of water. The Moken’s strong cultural identity, developed on the water, is being forced to adapt to new environments. Some now live in thatched huts elevated on stilts driven into the mud. Still, they seldom venture any distance inland from the beach. Boat dwellers don’t have much business on land.

As the world changes around them, the Moken are slowly disappearing. But, for as long as they survive, they seem to be sublimely impervious to the despair occurring in the rest of the world. Many cultures like theirs persist under the gun, seemingly impossibly, because genetically they don’t know when to quit. In this lonely dockside corner of Asia, knotty vitality breathes, even on the fringe of a country that’s typically at war with itself. As the kabang floats away, a teenager on board turns around, waves faintly, and lends one more Moken moment.

There is no way to harmony. Harmony is the way.

The sunrise is a stronger symbol than the sun setting on Burma’s departing sea gypsies. The winds are watching. As the boat disappeared into the horizon, I wonder if life at sea will outlast life on land.

– – – – –

I first encountered the Moken in 2001. During the 2004 tsunami that devastated the Indian Ocean shoreline, Burma was also flooded. Because Moken teachings hinge on ancestral storytelling, their elders knew that the initial, extraordinary low tide retreat of the sea indicated that a tidal wave was imminent. As a result, most Moken families immediately retreated to higher ground and were spared.

{a moment from The Directions to Happiness: A 135-Country Quest for Life Lessons}