How One Guitar Will Save The World

An Interview with Luke Maguire Armstrong—The Nomad’s Nomad

Rarely does a written story make me laugh out loud, but did just that. So, I emailed the author. A few months later, I met Luke Maguire Armstrong, a guy who, in the midst of hitchhiking from Chile to Alaska, got happily stuck in Guatemala for four years. Since then, we meet whenever he breezes through New York City.

I wrote about life on the road while traveling pretty much constantly for 20 years until mellowing into “home life,” which now means taking 10 disconnected trips a year—with each trip now having predetermined return dates. Those vagabond years defined me and make me a tough customer when it comes to enjoying a travel tale. I know a lot of travel writers, but only one who is truly, almost constantly still out there. As opposed to the long-weekend warriors attempting to take over travel writing via minute-by-minute blogging, lives on the road and patiently crafts tales that stand the test of time. The author of supports himself by writing, playing music, and spearheading ongoing humanitarian efforts in Guatemala, Uganda, Kenya, and New York. Recently, we sat down for a chat in Bushwick, Brooklyn, while he paused between a stint in Iceland, where he started the band “Loki and the Fashion Bandits” and a return to one of his first loves, Guatemala.

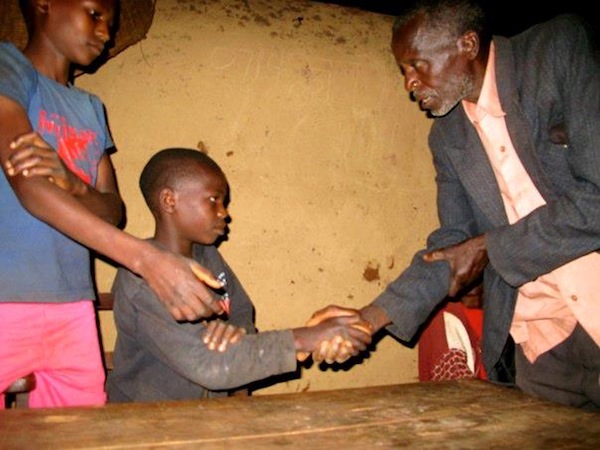

When it seemed my plan was falling apart. A year ago this month, I arrived from Nairobi to New York City after three months in Kenya covering the 2013 elections as a freelance journalist and working pro-bono to put two children orphaned by AIDs in school. I returned to NYC worse than broke. My trip to Kenya, that was supposed to earn me an income, left me $5,000 in credit card debt. I had fifty bucks cash in my pocket and a friend’s couch to sleep on for a week or so.

That marked my one-year anniversary of trying to make the mobile writer lifestyle work. I paced that small Brooklyn apartment and looked at my guitar. She looked back as if to say, “Don’t look at me, this is the life you made for yourself.” I swore silently and made a decision to cut off my lifeboats. I decided then that if I made $100 a month doing what I loved, then that was what I lived off. If I wanted to have a life more glamorous than a homeless person’s, I was going to have to work harder and smarter. I spent my last $50 on business cards, opened my laptop, started writing, and stopped looking back.

Q. Most people might have thrown the towel in well before that point, what caused you to stick it out so long?

I needed that gun to my head—that Yoda on my shoulder telling me, “Do or do not, there is no try.” When failure is not an option, your success is measured by degree. Also, “coming of age” in the expatriate scene of Antigua, Guatemala, made a nomadic life seem like a logical next step.

Q. What prior experiences led you to that small Brooklyn apartment?

While finishing my last semester of college as an exchange student in Chile in 2007, I read the book Into The Wild, took the wrong message from it, procured a $7,000 student loan, ditched my return ticket home, and started to hitchhike from Chile to Alaska. My family has a rich history making rash decisions abroad that affects the course of everyone’s lives—my parents met in the Marshal Islands as Peace Corps volunteers and decided to get married after a few weeks of dating. Near that time, my dad was thrown out of The Peace Corps for building a radio station instead of a tomato garden.

My plans on the road were to volunteer along the way and begin earning a living as a writer before my student loan ran out. I met an Irish travel writer at a campfire on a beach on the Caribbean coast of Colombia, and he told me, “Do what you want to do in life. There will be always someone who will pay you for it.” We’ve all heard some variation of this, but at the time I was 22 and it was my first time. It was an exciting notion. I listened to the lapping of waves and thought about my peers. It seemed like most of them put off doing what they really wanted to do to some future date. I never really bought into that model as viable for life and have always been happier for it.

Book-length story short, I thought my writing would support my humanitarian habit, but for four years my humanitarian work supported my writing habit.

Many thought taking out that $7,000 student loan to travel was a dumb plan, but in the end it led to a career that paid off that loan and most of my others. For four years, I worked in Antigua, Guatemala, as the program director for the charity Nuestros Ahijados. My 11th day volunteering at the project, the director quit and the executive director and founder somehow thought giving me, a 22-year-old, the position was a good idea. I administered 12 programs, fund-raised to meet the budgetary gaps that most NGOs suffered in 2008, and managed a staff of 50 employees and 500 annual volunteers. The project provided education and health resources for people to break out of poverty and had a program to rescue victims of human trafficking. It was a wonderful job where every day felt impactful, and I can’t imagine living life today without the many lessons I learned from that opportunity. In 2010, Christiane Amanpour came to Guatemala to interview me about a and ran for Nuestros Ahijados.

Q. Because you’ve worked with traveling women victimized by crimes in places like Central America, I imagine you would be the right guy explain the rules of the road to my daughter in a few years. What is your core advice to women traveling in distant lands?

Aside from warning them to stay away from my friend Andres, I would say women travelers by the unique nature of the dangers they face are far ballsier than their male counterparts traveling the same road. Be smart ladies, and trust your instincts. No, be smarter than smart. Be a femme fatale traveling Jedi warrior woman who is always one step ahead of anyone that would harm you. You don’t need to actively distrust strangers—most people are good. But never trust anyone you’ve just met 100-percent. People who want to hurt you or take things from you use your trust as their camouflage.

Do your research. What does the guidebook say about safety? What do expats know? What do other travelers say? What do the locals know? What does your embassy say? All of these sources should be looked into, because each provides an important piece to the puzzle of how safe a place is and what you should do to avoid the dangers. If the streets aren’t safe at night, get yourself a reliable cabby who doesn’t drink on the job. If that doesn’t fit into your budget, give your pops Bruce a pouty face and remind him how much he loves you, and I bet he’ll grab your taxi bill. He would have just spent it on beer anyway. Speaking of beer, don’t leave your drink unattended, and don’t accept a drink that you did not watch the bartender make.

Q. I would imagine that playing music live puts you on a fast track into cool, wild, or bizarre situations. Does it?

I’m not sure if it’s my guitar or the crazy person playing it (see Luke perform), but the short answer is yes. Playing the guitar is a great way to meet people and gain access to places. Most of the stories stemming from this fact are long. One short story that comes to mind is when my guitar led me to an underground gambling ring of chicken bus drivers in the lakeside village of San Pedro, Guatemala. My guitar and I were both drunk. The rest of my friends had gone to bed at a reasonable time. My late-night guitar playing by the lake led to a man named Juan approaching me and inviting me to this underground gambling ring he knew of on the outskirts of town.

It looked like a tough crowd and a rough game. I made a point of losing $20 to keep them from pulling out the guns I could see bulging from their belts and just taking what they wanted. It could have gone even more loco, because one of them asked me if I would be his “frog”—the guy on the bus that collects the money and shouts out the destinations. He was drunk and about to drive to Xela, Guatemala. It was 5am. He said he could get me back by noon. This was a very tempting offer. I did not have a phone with me to inform my friends at the hotel why I would have failed to materialize in the morning, so I declined. I took a few more shots of the fire water the bus driver insisted I try and called it a night just as the dawn ticked up on the horizon.

Q. What’s next for you? You say you’re committed to the path you’re on now, but what specifically is that path?

It’s a winding one, and there are always surprises on it. I plan to continue to write and continually take that craft to a new level. I am finishing a non-fiction book about my four years living in Guatemala and courting various publishers for my completed novel How One Guitar Will Save The World.

Humanitarian-wise, I am going to continue to fundraise and deploy that capital with charities that I have vetted as being sustainable and making tangible differences. My music has recently taken on a life of its own, and I have an LP coming out soon called “Luke Maguire Armstrong: Eaten By a Horse.” Oh, and we can’t forget women. I hope to run into some of them. Specifically, I hope to meet one as crazy as I am, who will let me buy a puppy to “nip at our heels.”

– – – – –

frequent contributor to an award-winning site with the best travel stories from wandering book authors. His current project, is an effort to raise $10,000 to take 55 children off the streets in Guatemala and place them in school.